Space-Based Early Warning Systems (SBIRS & DSP)

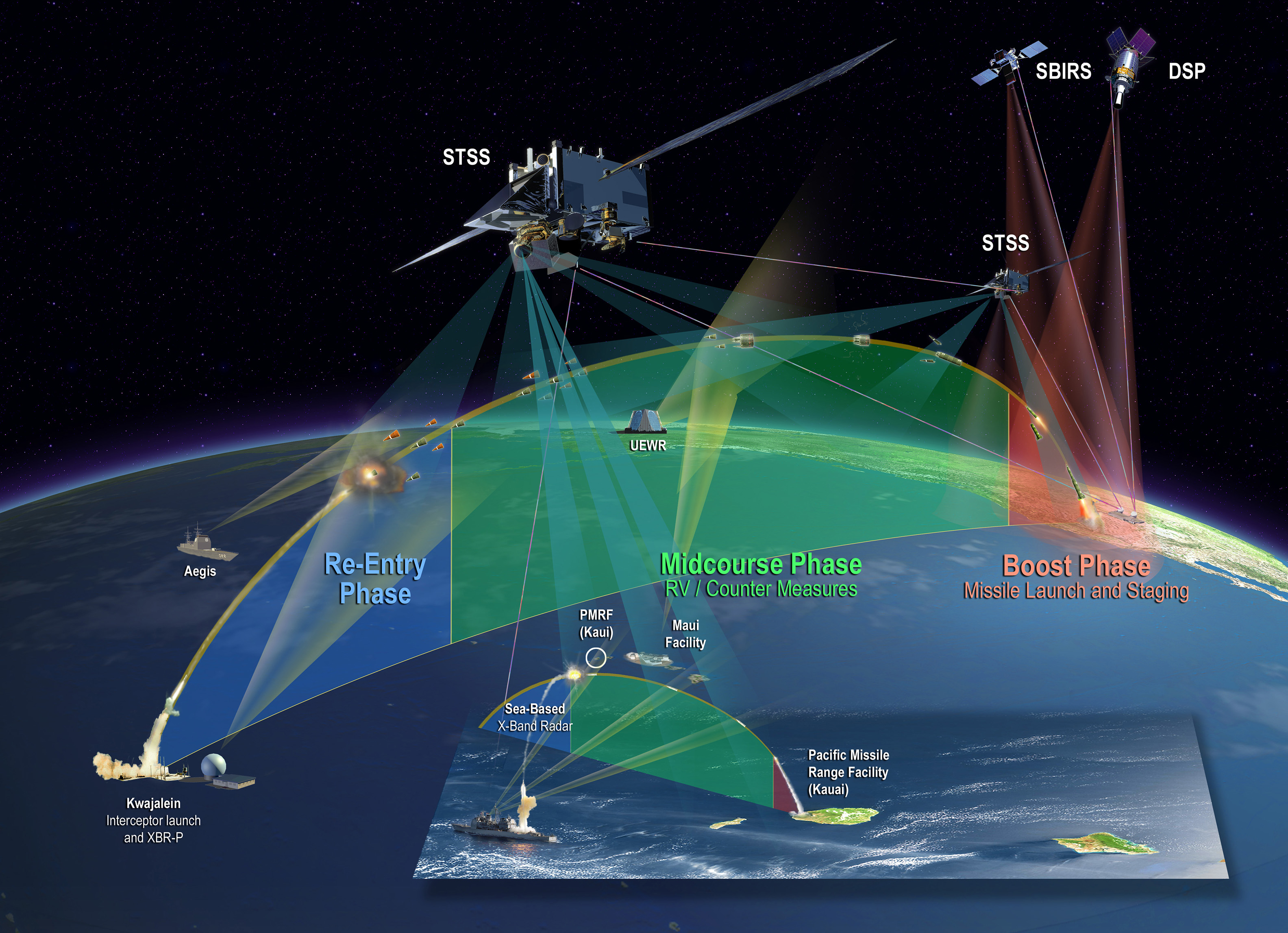

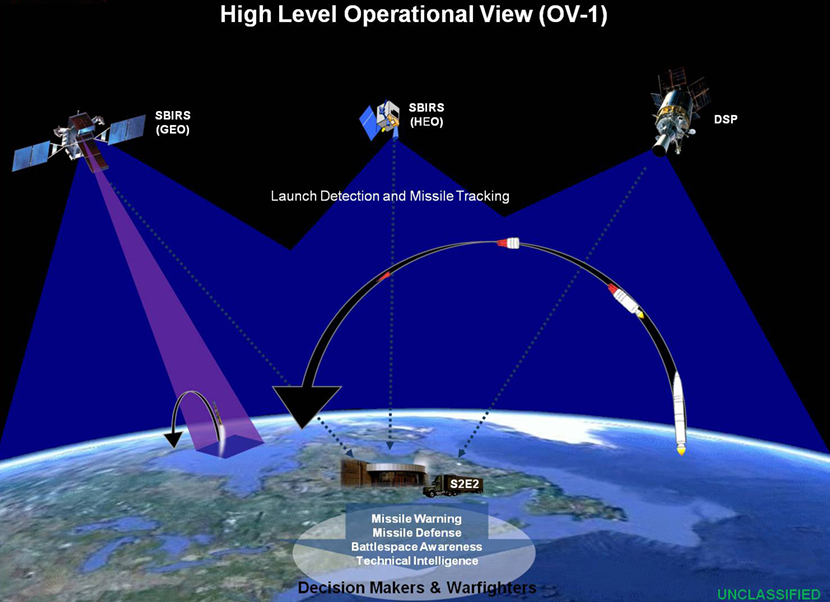

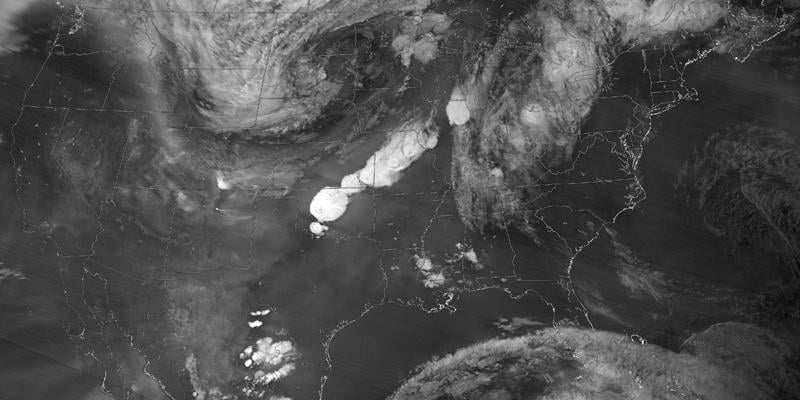

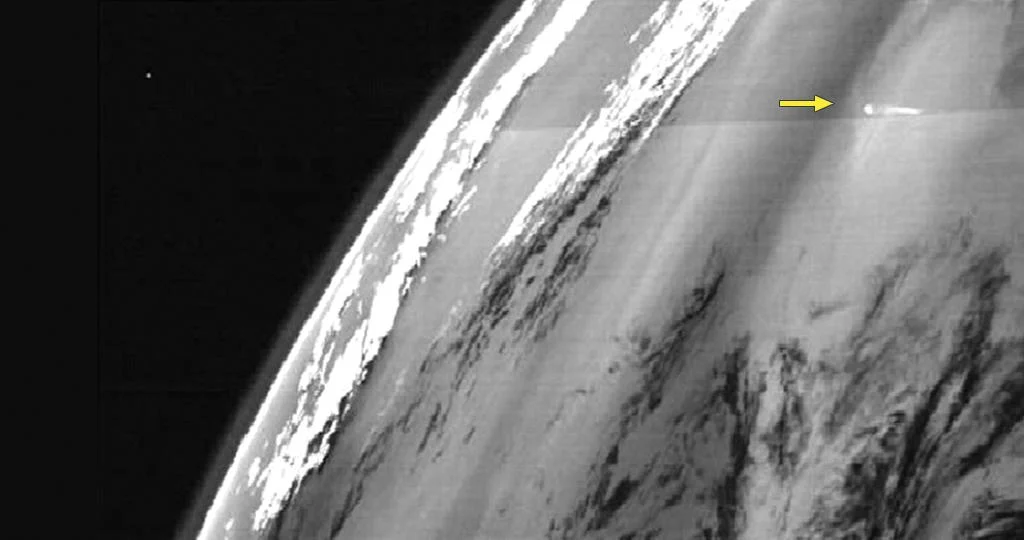

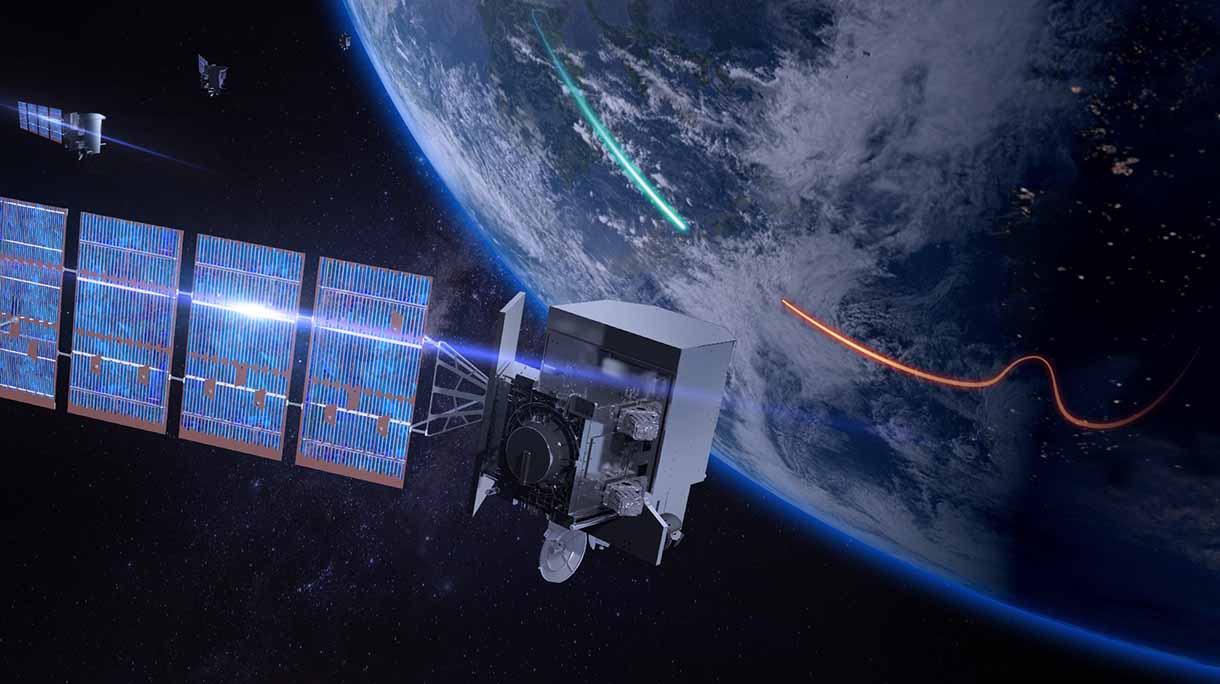

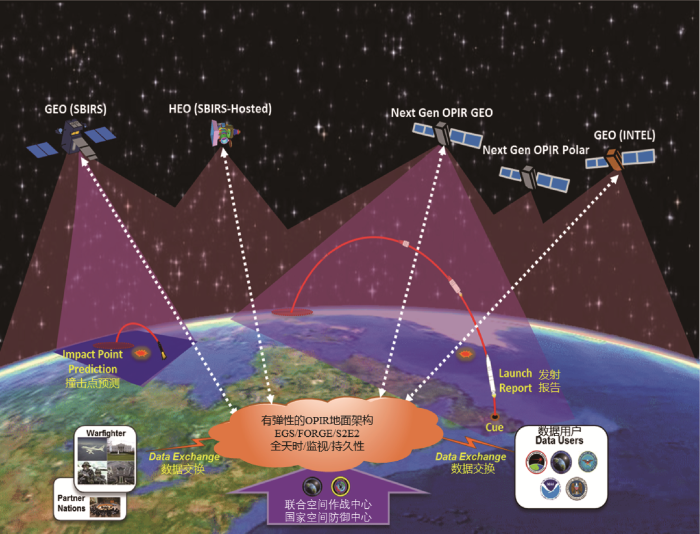

Space-Based Early Warning Systems (SB-EWS) are a critical component of the anti-ballistic missile defense architecture employed by global powers. These systems utilize specialized satellites equipped with infrared sensors to detect ballistic missile launches from both land-based and naval platforms. Once a launch is identified, the system tracks the missile’s trajectory during its midcourse phase. The collected data is then transmitted to ground-based missile defense networks, enabling timely response and precise interception capabilities.

In January 2020, U.S. forces across West Asia were on high alert, anticipating a retaliatory strike from Iran following the assassination of Major General Qassem Soleimani. During this period, SBIRS satellites began monitoring Iran’s missile launch sites. Infrared sensors detected launch signatures and precisely tracked the flight paths and potential targets of the missiles. The data was swiftly relayed to U.S. forces stationed in Iraq. Similar procedures were repeated during operations “True Promise” and “Glad Tidings of Victory,” with Iranian ballistic launch data shared with U.S. forces in Qatar, the Red Sea, the Mediterranean, and Israel.

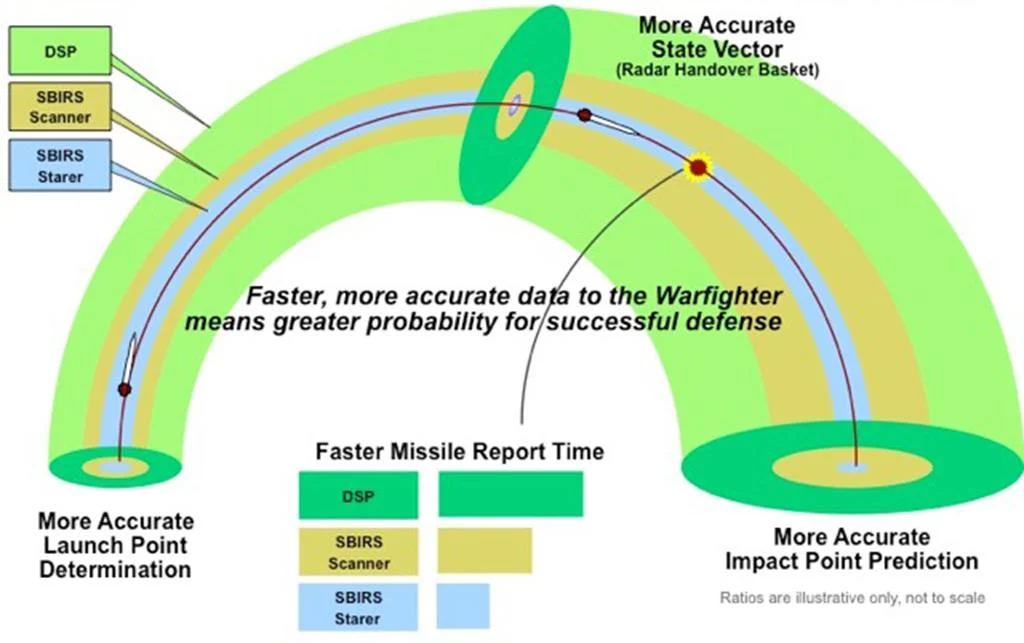

Importance of Space-Based Early Warning Systems: Since the 1950s, early warning of potential attacks on the U.S. has been a central concern of its military space program. Research showed that space-based systems could extend the warning time for intercontinental missile launches from 15 minutes to approximately 27 minutes, nearly doubling the alert window for long-range launches. Unlike conventional radar sensors, these systems can detect low-altitude nuclear warhead flights (FOBS) in orbital bombardment scenarios and validate radar data. Their use reduces false alarm rates and offers better cost-effectiveness compared to ground-based radar systems. With these advantages, the U.S. has prioritized space-based systems for over six decades, deploying them today against threats from Russia, China, North Korea, Pakistan, and Iran.

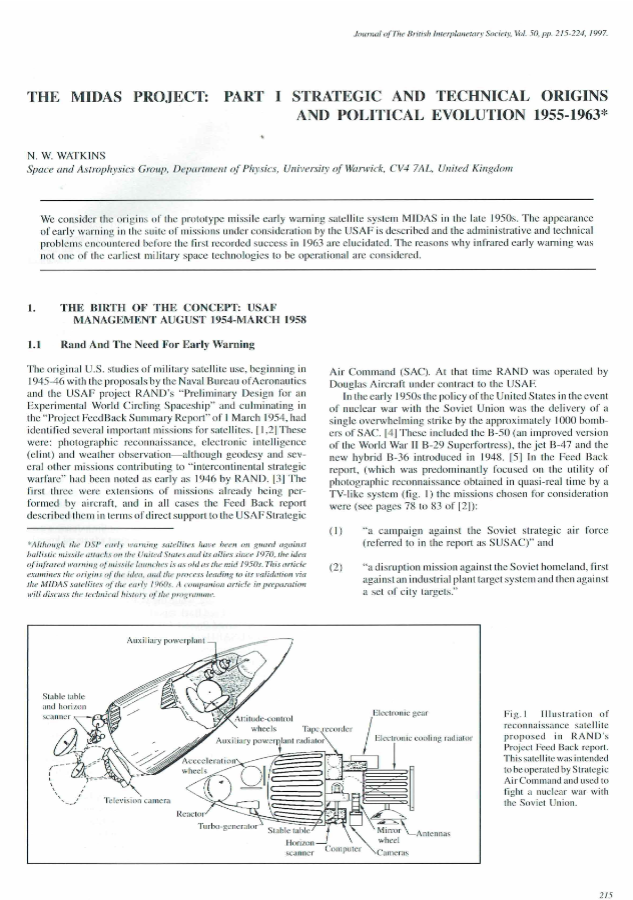

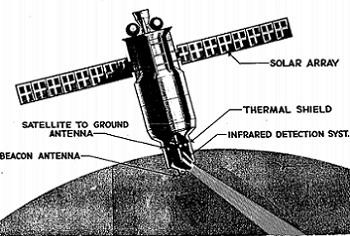

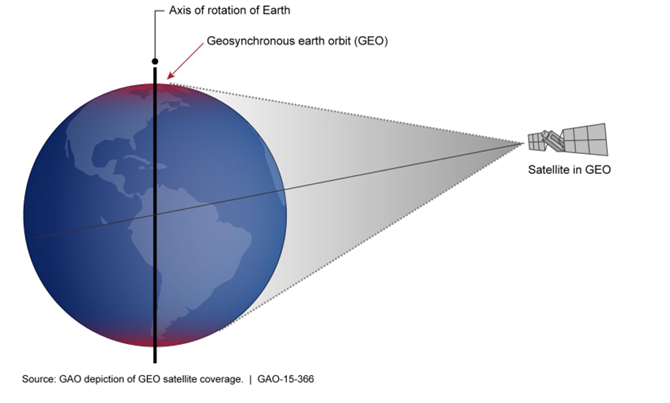

Origins: America’s first efforts to develop infrared early warning satellites began in the 1960s with the Midas project, which operated in low Earth orbit (LEO). However, the conceptual roots trace back to a late-1940s proposal involving a satellite equipped with an infrared radiometer and a space surveillance telescope. Midas later evolved into Project 461, tested between 1963 and 1966. Studies revealed that global coverage in LEO would require around 20 satellites, while highly elliptical orbit (HEO) configurations needed only 9 to 10, and geostationary orbit (GEO) could achieve full coverage with just two satellites—one per hemisphere. However, GEO demanded highly sensitive infrared sensors to detect launches from great distances. Consequently, the U.S. Air Force deemed GEO-based systems the most technically and economically viable. Starting in 1965, Projects 461, 266, 949, and ultimately 647 laid the foundation for the Defense Support Program, though detailed descriptions of each project fall outside the scope of this discussion.

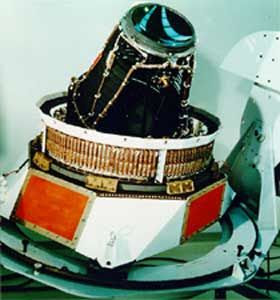

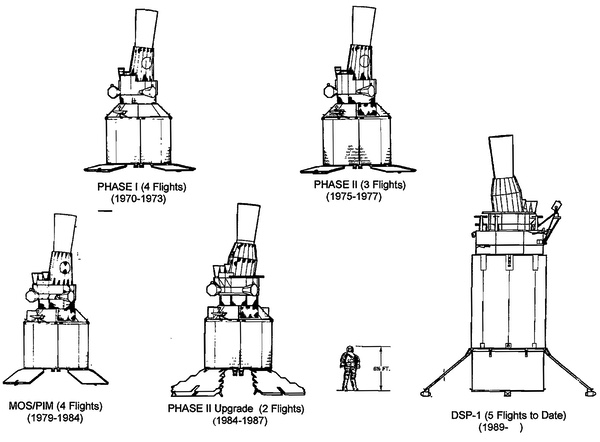

With the completion of initial research, the first-phase contract for the Defense Support Program (DSP) was valued at approximately $105 million and included the construction of three satellites, each weighing 907 kilograms with an estimated operational lifespan of 19 months. Initially, two satellites were deemed sufficient, but due to the threat posed by Soviet submarine-launched missiles, the number was increased to three operational units. Each satellite covered distinct regions: the Atlantic Ocean and eastern Pacific, Soviet and Chinese missile fields along with the Indian Ocean, and the western Pacific.

In subsequent phases, both the weight and lifespan of the satellites increased. By 1970, their mass reached around 1,000 kilograms with a 3-year operational life. This development continued through five phases, and in later generations, the satellites weighed up to 2,300 kilograms and operated for 5 to 10 years.

Between the 1970s and 2007, a total of 23 DSP satellites were launched into geostationary orbit. During this period, typically 2 to 4 satellites were active in orbit at any given time.

Performance Review: The system proved highly effective; these satellites were capable of detecting missile launches, space launches, and even nuclear detonations via infrared signatures. DSP satellites played a crucial role during Operation Desert Storm by identifying Iraqi Scud missile launches.

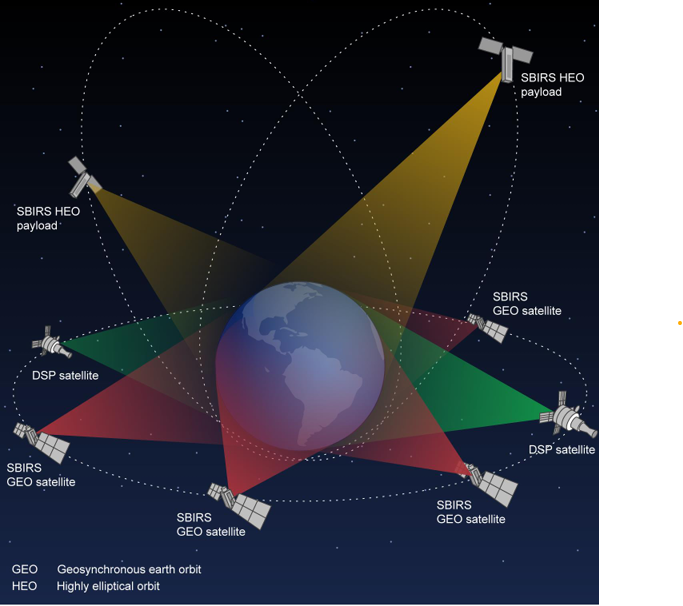

Ultimately, with the rapid advancement of missile technologies, the need for a replacement system emerged, and the final DSP satellite was launched in 2007. However, three DSP satellites remain active today under the operational framework of the U.S. Space Force.

Many experts believe DSP did not operate alone. Another infrared detection system, mounted on a classified satellite in highly elliptical orbit (HEO), also contributed data. This system, generally referred to as “DSP-Augmentation,” provided overlapping coverage and a different viewing angle compared to DSP satellites positioned above the equator.

Ground-based integration of multiple data streams enabled a more comprehensive understanding of targets. Yet, almost no public information is available about DSP-A.

Dawn of a New Generation: The SBIRS (Space-Based Infrared System) program was officially launched in the mid-1990s to replace the aging DSP satellite constellation. However, its path to becoming a fully operational system was fraught with challenges. By 1996, the U.S. Air Force had signed a contract to develop the SBIRS-High system. In 1999, concerns over the Y2K bug intensified, as many military and civilian systems were unable to correctly process the year 2000, raising fears of software failures. As a result, the goal was to launch the first satellite of the new constellation by 2002 and fully replace the previous system with a far more advanced one by 2010.

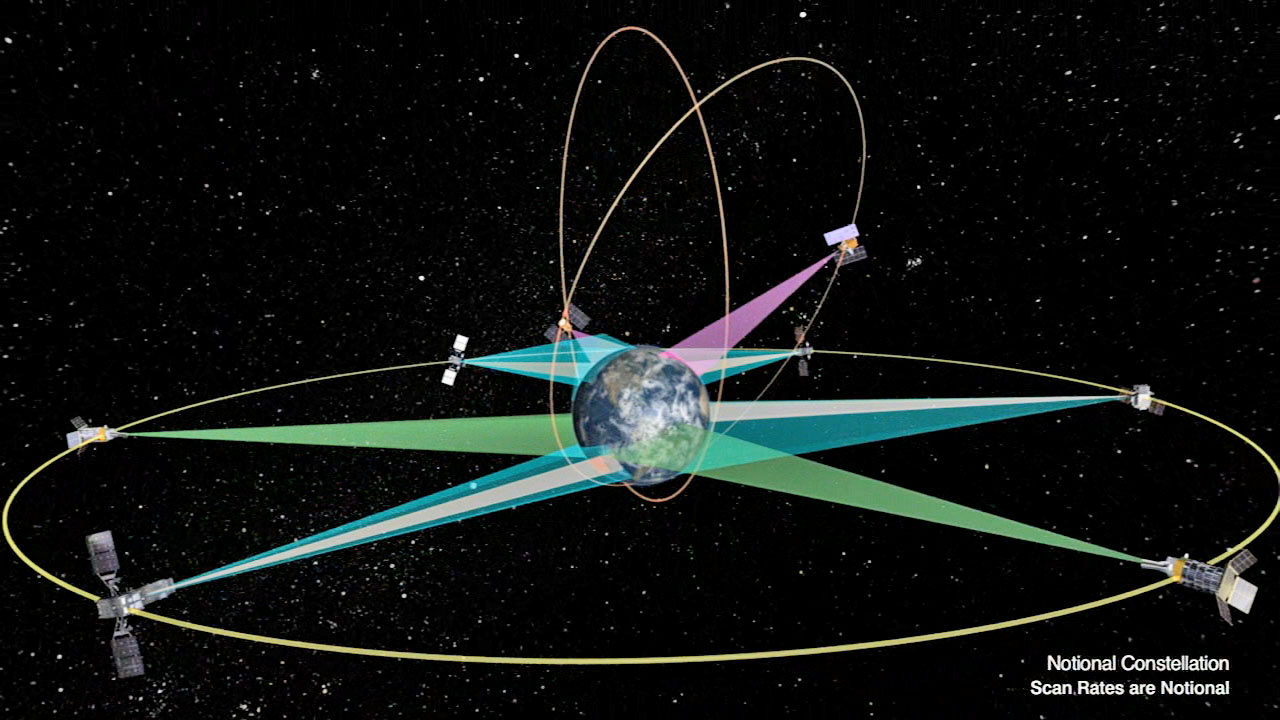

The initial plan included a SBIRS-High constellation with satellites in geostationary (GEO) and highly elliptical orbits (HEO), followed by 24 separate satellites in low Earth orbit (LEO). The concept was for SBIRS-High and SBIRS-HEO to detect launches early, while SBIRS-Low would provide precise midcourse tracking of missiles in space, enabling warhead interception.

However, in 2001, the SBIRS-Low program was transferred to the Missile Defense Agency and evolved into the Space Tracking and Surveillance System (STSS), which focuses on tracking ballistic missiles throughout their flight path.

Challenges in the Early 2000s: During the early 2000s, the SBIRS program faced serious setbacks. The U.S. Air Force encountered technical issues, delays, and cost overruns across all three segments of the system. The program’s budget ballooned from $2.1 billion to $9.9 billion. The launch of the first satellite was postponed from 2002 to 2004, and then again to 2006.

In 2006, the first payload in highly elliptical orbit (HEO) was launched, followed by a second in 2008, and two more in 2014 and 2017. These HEO payloads replaced the DSP-Augmentation system. Eventually, the first geostationary (GEO) satellite was launched in 2011—nine years later than originally planned.

Throughout this period, the legacy DSP and DSP-Augmentation systems (classified infrared sensors in elliptical orbits) continued to serve as the backbone of space-based missile warning. In practice, few expected DSP to remain operational for another decade.

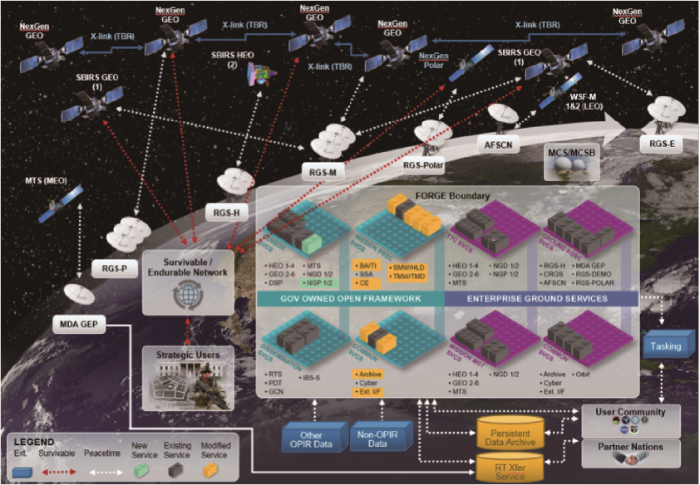

System Architecture: This constellation forms a resilient, multi-layered network designed to deliver comprehensive, continuous, and timely missile launch warnings on a global scale. It consists of various components operating across different orbital regimes, each tailored to specific mission requirements. All segments are managed and processed through a unified, modern ground system that ensures coordinated functionality and data integration.

A Key Driver of Final Architecture: One of the pivotal events shaping the final architecture of SBIRS was China’s 2007 anti-satellite test, which exposed vulnerabilities in geostationary satellites. This incident underscored the importance of retaining the last three operational DSP satellites as backup assets.

As a result, SBIRS was structured to integrate its dedicated satellites, hosted HEO payloads, and legacy DSP satellites under a unified ground control system managed by the mission station at Buckley Space Force Base in Colorado. This integration consolidated all active space-based early warning assets into a single operational framework. By fiscal year 2018, all missile warning activities were unified under the SBIRS designation.

Data Flow and Processing: Data from satellites is transmitted via five hardened downlink channels. Raw sensor data is received on the ground and undergoes complex signal processing to identify and classify potential events. The processed information is then relayed as alerts to the command chain, including the National Space Defense Center and USSTRATCOM.

This integrated structure allows satellite data to be fused with other sources—such as upgraded early warning radars (UEWR)—to produce a comprehensive and accurate battlespace picture.

Military Knowledge: AEGIS Defence System; Standard Missiles

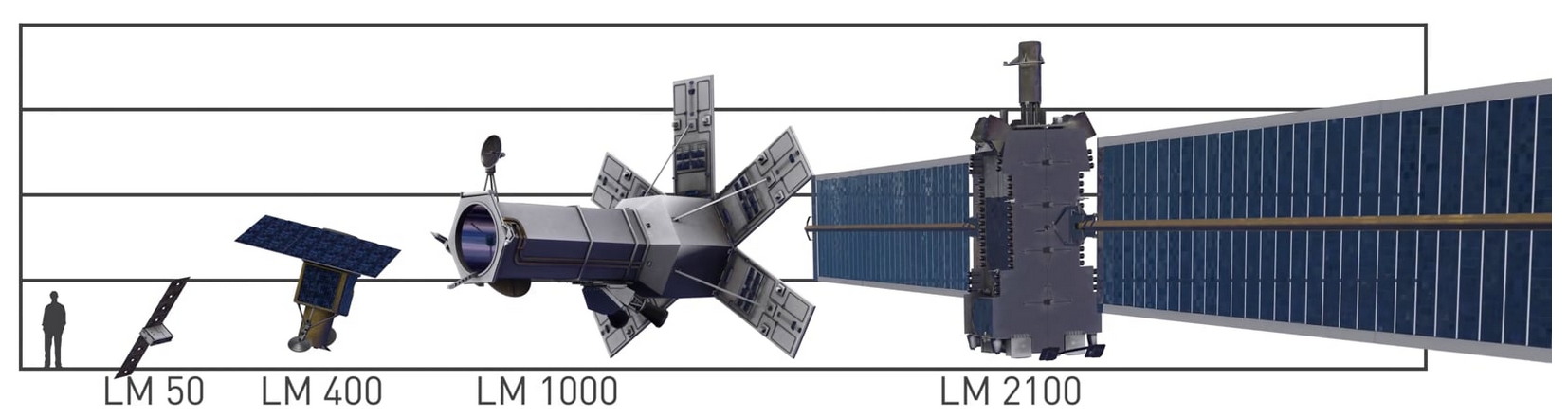

Satellite Configuration: The space segment of the constellation includes satellites in geostationary orbit and infrared sensors hosted on other satellites in highly elliptical orbit. The GEO constellation consists of six dedicated satellites—GEO-1 through GEO-6—built by Lockheed Martin on the LM2100 Combat Bus platform. Positioned approximately 22,000 miles above Earth, they provide continuous surveillance of mid-latitude regions.

Dual-Sensor Payloads and Satellite Capabilities: Each SBIRS GEO satellite carries a dual-sensor payload:

- A scanning sensor for wide-area strategic missile warning

- A staring sensor for high-sensitivity, rapid-revisit surveillance of specific regions

This configuration offers triple the sensitivity, double the resolution, and twice the revisit rate compared to DSP satellites. The sensors operate across both shortwave infrared (SWIR) and expanded midwave infrared (MWIR) bands, enabling detection of a broader range of threats—including dimmer missiles or those with shorter burn times.

Onboard signal processing allows GEO satellites to analyze raw data and transmit only confirmed events, reducing downlink volume and accelerating alert delivery. The first two satellites were launched in 2011 and 2013, followed by additional launches in 2017 and 2018, and the upgraded pair GEO-5 and GEO-6 in 2021 and 2022.

Platform and HEO Sensors: The LM2100 platform features enhanced cybersecurity, increased power capacity, and improved propulsion systems. In addition to GEO satellites, SBIRS includes four HEO sensors hosted on other government or commercial satellites.

Due to their highly inclined orbits, HEO sensors are especially suited for detecting submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) from the Arctic region—where GEO coverage is limited. The first two HEO payloads were launched in 2006 and 2008, exceeding performance expectations, followed by two more in 2014 and 2017.

These sensors use gimbal-controlled telescopes, allowing independent targeting of specific regions for optimized coverage.

The concluding chapter of the SBIRS program was marked by the launch of GEO-6 on August 4, 2023, completing the full deployment of the SBIRS constellation before transitioning to its successor, Next-Generation Overhead Persistent Infrared (Next-Gen OPIR). Throughout its lifespan, the program was overseen by various U.S. Department of Defense entities, including the Air Force Space Command, the United States Space Force, and the Space and Missile Systems Center. Lockheed Martin served as the primary contractor, while Northrop Grumman provided the sensor payloads as a subcontractor.

Future Development: For over a decade, the SBIRS system has served as the cornerstone of the United States’ missile warning capability. However, the threat landscape has evolved. A constellation originally designed to counter traditional ballistic missile threats now faces emerging challenges such as hypersonic weapons, jamming systems, and modern space-based attacks. This shift is the primary driver behind the Next-Generation Overhead Persistent Infrared (Next-Gen OPIR) program—a system that incorporates more capable geostationary satellites, polar-orbiting platforms, and distributed sensors in low and medium Earth orbits.

The new architecture is more resilient, survivable, and less vulnerable to single points of failure. Its sensors offer three times the sensitivity and twice the accuracy of SBIRS, along with quadruple the downlink bandwidth to enable precise tracking of maneuverable threats.

Ground Segment – FORGE: Equally important is the FORGE ground system, which plays a vital role in sustaining the U.S. missile warning and tracking mission. As SBIRS nears the end of its planned lifecycle and is gradually replaced by Next-Gen OPIR, FORGE acts as a critical bridge—ensuring seamless integration of new capabilities while maintaining operational continuity.

FORGE is designed to replace legacy ground systems. This consolidation reduces costs, boosts efficiency, and eliminates the burden of maintaining multiple incompatible platforms. With an estimated investment exceeding $3 billion for the FORGE component alone, it is clear that modernizing the ground infrastructure is considered one of the most strategic investments in the future of U.S. space domain awareness.

Transition Timeline: The first launch of a Next-Gen OPIR satellite is scheduled for early 2026. Meanwhile, FORGE’s role as a unified backbone for data processing and distribution enables it to support both legacy SBIRS assets and next-generation systems simultaneously.

As a result, the legacy of SBIRS—trusted and battle-proven—paves the way for a more resilient, responsive, and adaptable space architecture under Next-Gen OPIR.

Assessment of Limitations and Challenges: For over a decade, the U.S. space-based infrared system has served as America’s vigilant eye in orbit, playing a vital role in missile warning and situational awareness. However, the system’s inherent limitations against emerging 21st-century threats have gradually come to light. SBIRS was originally designed to track ballistic missile launches—not to continuously monitor hypersonic weapons or maneuverable warheads that fly at low altitudes after booster burnout. These targets typically travel between 30 to 50 kilometers in altitude with unpredictable flight paths, making them difficult for current systems to detect. Additionally, cruise missiles often evade overhead sensors due to their weak infrared signatures.

With the rise of multidimensional threats from Russia and China, ensuring the survivability of this system has become a strategic priority for the United States. Physical threats such as anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons, orbital interference, and directed energy attacks all pose risks of disabling or destroying satellites. Successful ASAT tests by China in 2007 and Russia in 2021 demonstrated that even GEO orbit is no longer secure.

To counter these threats, SBIRS incorporates redundancy in its architecture: six GEO satellites and four HEO sensors provide a degree of fault tolerance, ensuring that the loss of one or two satellites won’t cripple the entire system. Moreover, the newer GEO-5 and GEO-6 satellites, built on the LM2100 bus, offer enhanced power, propulsion, and agility to maneuver away from hostile encounters.

Beyond Space – Ground Vulnerabilities: Threats aren’t limited to orbit. The system’s ground infrastructure and command network—including the Mission Control Station (MCS) and the FORGE ground system—are exposed to sophisticated cyberattacks. Any breach could corrupt data or jeopardize satellite control. The 460th Cyberspace Squadron at Buckley Space Force Base is tasked with defending the OPIR network against such intrusions.

The 2022 cyberattack on Viasat’s KA-SAT network, which disrupted satellite communications across Europe and the Middle East, serves as a stark reminder of this reality. In addition to kinetic and cyber threats, non-kinetic dangers such as radio frequency jamming, high-power microwaves, and infrared lasers can blind or damage sensitive satellite sensors.

Compounding these risks is the growing challenge posed by hypersonic weapons. These systems travel in short, depressed trajectories, with dimmer and shorter booster burn phases—making them significantly harder to detect with existing infrared sensors.

Comment