Behind the Scenes of the Julani–Kalin Meeting: From the March 10 Agreement to Israel’s No-Fly Zone Proposal in Southern Syria

The recent meeting in Damascus between Abu Mohammad al-Julani (Ahmed al-Sharaa), head of Syria’s interim government, and Ibrahim Kalin, chief of Turkey’s National Intelligence Organization (MIT), has reignited attention on Syria’s evolving political landscape and the flurry of regional and international negotiations surrounding it. The timing of this meeting—just days after Israel proposed a no-fly zone in southern Syria and following visits by U.S. envoy Tom Barrack and Jordanian Foreign Minister Ayman Safadi—suggests a coordinated diplomatic effort rather than coincidence.

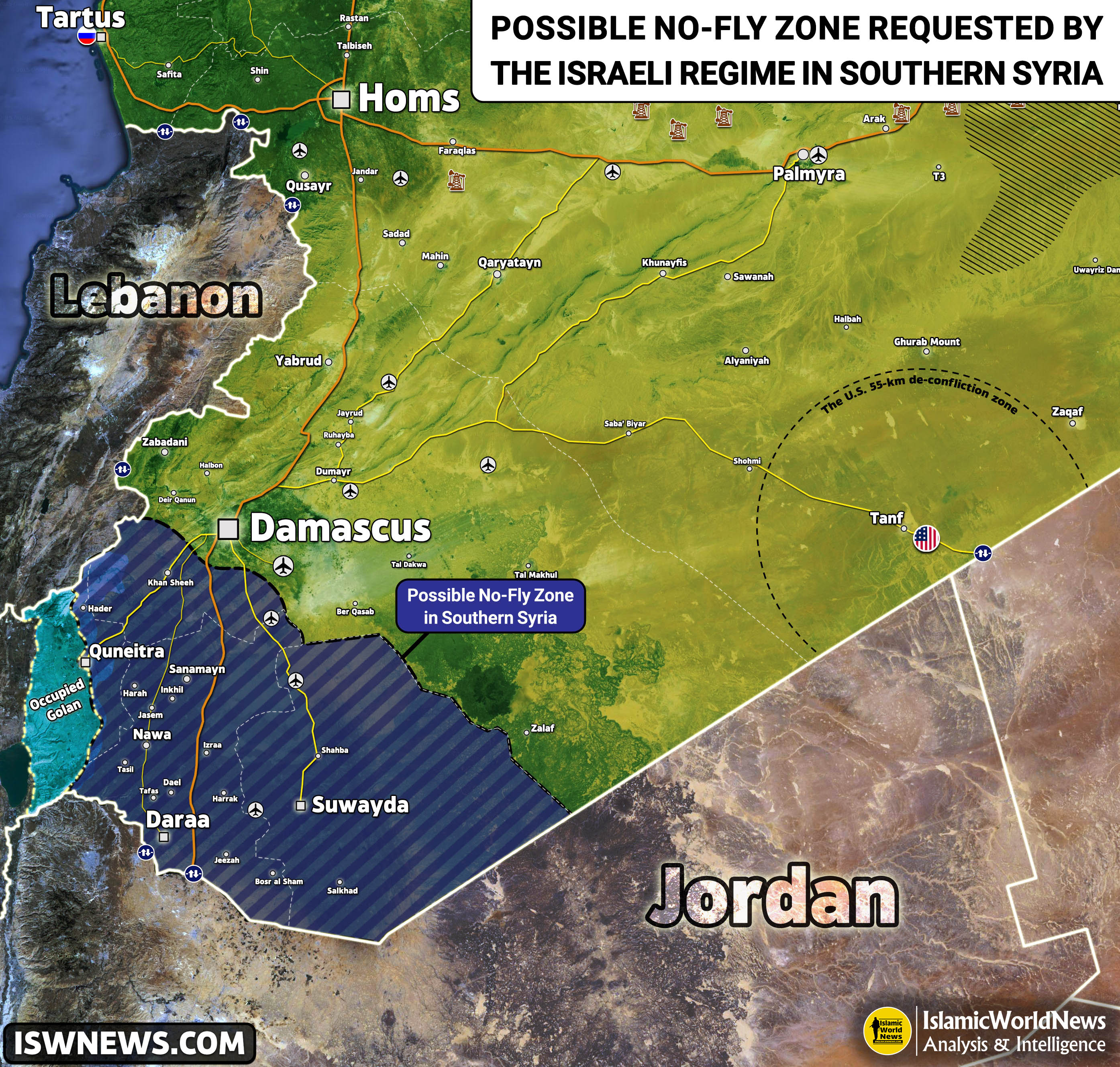

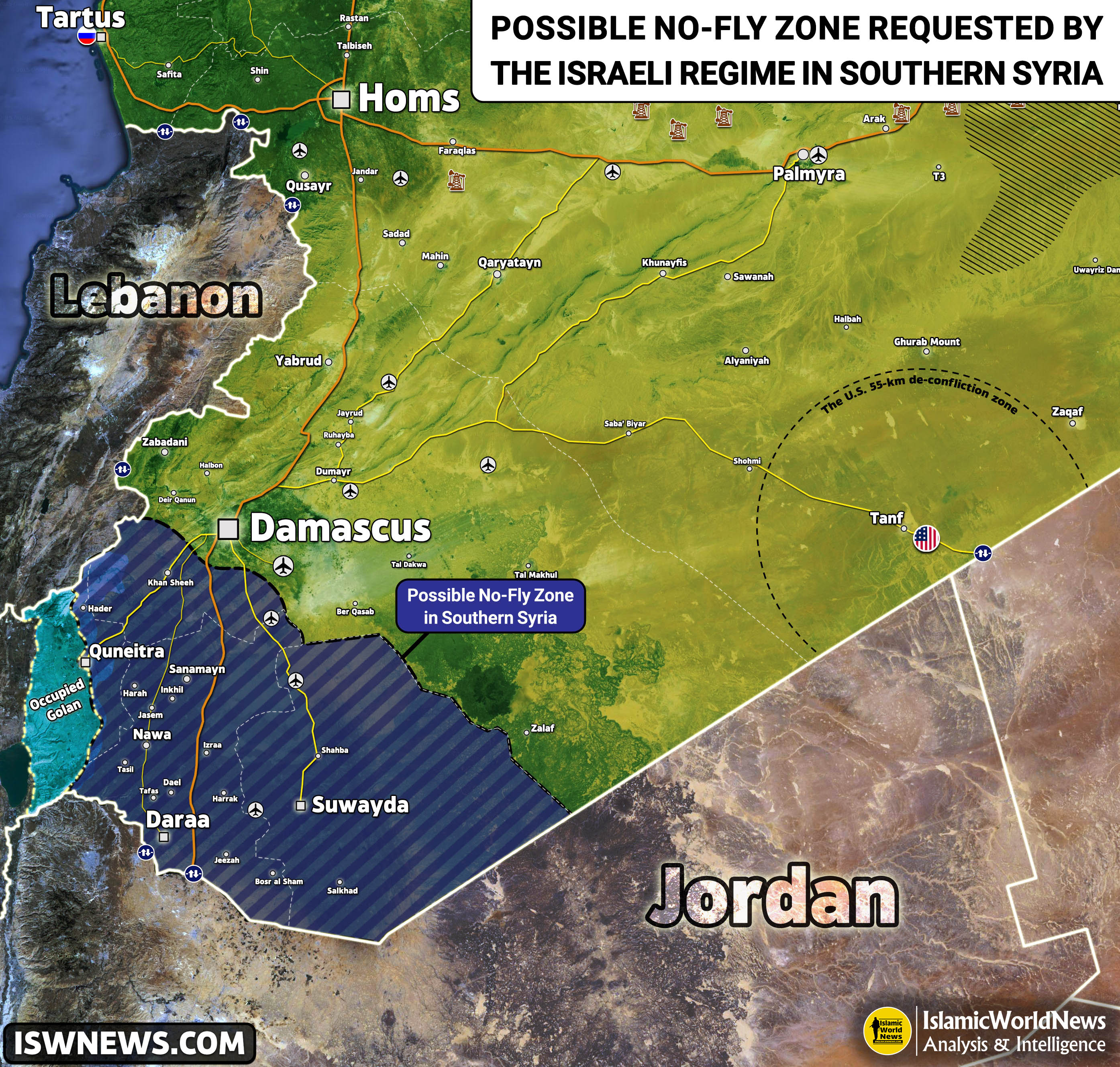

According to Western sources, Israel has presented Damascus with a new security proposal. The plan includes establishing no-fly zones over parts of southern Syria while preserving an aerial corridor from Syria to Iran. This corridor is strategically vital for Tel Aviv, potentially allowing future airstrikes on Iranian targets. The proposed no-fly zone would cover Suwayda, Daraa, Quneitra, and parts of Damascus. In exchange, Israel would withdraw from some areas it recently occupied in southern Syria—but notably, it refuses to pull back from Mount Hermon.

Meanwhile, Syria’s new government is expanding its diplomatic outreach, engaging with figures like Tom Barrack, Ayman Safadi, and representatives from Gulf Arab states. These interactions suggest Damascus is working to build a multilayered network of security and political alliances. The goal appears to be reducing international pressure while gaining flexibility in dealing with local forces (such as the SDF) and regional powers like Turkey and Israel. Al-Julani, at the helm of this effort, seems intent on balancing U.S.-Israeli demands with Turkey’s red lines.

In the context of ongoing tensions between Iran and Israel, Tel Aviv’s proposal for Syrian no-fly zones is part of a broader strategy to secure a reliable aerial corridor toward Iran. The recent collapse of Bashar al-Assad’s regime and the destruction of much of Syria’s air defense systems have made Syrian airspace one of the least risky and most cost-effective routes for Israeli aircraft heading toward Iran’s western borders. Any agreement with Damascus could significantly enhance Israel’s operational capabilities against Iranian targets.

Another Israeli objective is to minimize the risk of direct confrontation with Turkish air forces. Turkey’s military presence in Syria—especially in air defense—has grown in recent months, increasing the chances of accidental clashes with Israeli jets. By negotiating a no-fly zone with Damascus, Israel aims to unilaterally manage Syrian airspace, impose its terms on both Ankara and Damascus, and reduce the likelihood of unintended military incidents.

If implemented, this plan would have wide-ranging regional consequences, with Israel standing to gain the most. It would solidify a permanent aerial threat against Iran from the west, restrict Turkey’s operational freedom in Syrian skies, and place Damascus under Israeli dominance. Although the Syrian government may not favor the proposal, the current military realities in southern Syria are pressuring Damascus to accept it.

Comment